Part I. “He thinks tis but our fantasy”: The Ontology and Epistemology of Ghosts and Spirits

In William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the skeptical and possibly Stoic Horatio reveals to the melancholic eponymous prince that he has seen a phantasm. Before Horatio can even reveal his harrowing yet problematic tale of seeing a “form like [Hamlet’s] father,” Hamlet declares, “my father–methinks I see my father” (Shakespeare Hamlet I.ii. 83). Despite Horatio’s apparent skepticism during and following his encounter with the phantasm of Old Hamlet, one senses apprehension in his uneasy response, “O where, my lord?” (84). Horatio, who, along with Barnardo and Marcellus, witnesses the appearance of a phantasm resembling the dead king in the first scene, confronts a melancholic prince who reports encountering another type of phantasm “in [his] mind’s eye” (84) of that same dead king in the second. Both visions present types of phantasm, and both relate to the faculty of the phantasy or imagination and to theories that explained ordinary as well as aberrant perception through phantasms or species. The two forms constitute different species of species or phantasm, but, in many theories of perception and cognition current in the later sixteenth century, they correlate and depend upon a similar explanatory system. While commentary assigned the phantasy an important role in mentally picturing objects or people that were not present before a perceiver, it also assigned the phantasy a special role in explanations of aberrant perception including those generated by a polluted body and those caused by witches and devils sometimes thought responsible for visions of the dead. Discourses on both of these forms of aberrant perception and on hallucination developed their explanatory systems through similar paradigms of the early modern sensorium, depending heavily upon a specific construction of the imagination or phantasy and the types of objects in which it mediated. We have two types of phantasms here that can be interpreted in a variety of ways, but those two types of phantasm or species might be closer than they initially appear.

Hamlet encounters the Ghost of his father.

Though largely ignored in early modern criticism, nearly every text explaining some aspect of perception and simple cognition in the sixteenth century draws upon the quasi-Aristotelian construction of the sensorium and often upon the Thomistic and Baconian notions of the species or phantasms to explain sensation, perception, and at minimum simple thought. This is true of the medical tradition as they crop up in authors as diverse as Andre du Laurens to Ambroise Paré, to Johann Weyer, to Helkiah Crooke, to Robert Burton. It is also true of discourses of demonology and witchcraft from Heinrich Kramer and Jakob Sprenger to Johann Weyer, to Reginald Scot, to King James. It is equally true, I argue, of literary texts which produced and were produced by these other traditions as explanatory systems within their pages or within their performances. I have already discussed their importance in some speeches from William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and, in this post, I turn to his Hamlet.

What does separate the two and the objects in both visions, those of Hamlet I.i. and I.ii.? We have a Ghost. We have Hamlet’s report of an image of his deceased father in his phantasy or imagination. One we see on the stage. The other remains forever invisible, inaccessible, and illusory. Both species or phantasms seem distinct and separable phenomena, but, if we look at discourses the sensorium and discourses on witchcraft in the sixteenth century in conjunction, we begin to see resemblances between Old Hamlet’s two types of appearance within the play. The phenomenon Horatio experiences in I.i. has external confirmation, certifying that his experience did not derive solely from his own mind, but Horatio remains reluctant to account the apparition a true spirit or ghost of the dead king. With the second type in the second scene, Hamlet knowingly pictures the dead king, his father, in his mind’s eye. While Hamlet’s mental phantasm of his dead father can only be revealed through Hamlet’s oral report, it is perfectly reasonable to assume that the character does indeed retain a phantasm of his father that, while supplemented by his private phantasy, conforms to and was produced by the actual presence of his Old Hamlet. Both discourses on the sensorium and those on witchcraft often draw from theories of the species, and both offer sometimes differing accounts about what actually happens when someone witnesses the appearance of a spectre, but both also typically rely upon the same underlying quasi-Aristotelian theory of sensation to explain both theories. Some authors accepted the real presences of ghosts and spirits, but many more, at least by the late sixteenth century, seem to question their reality, thinking them as Horatio initially does, as nothing “but… fantasy” (I.i. 21). While some allowed for the appearance of actual spirits of the dead, those ghosts are often discussed as appearing within the phantasy or imagination by offering or manipulating the species or phantasms within the faculty. Rather than the King’s two bodies, Hamlet presents us with the King’s two phantasms. While tangentially touching on the frisson caused by the death of the king’s natural body, the play also presents us with two of his phantasms.

The objects of the phantasy, the phantasms, like the sensible species to which they were related, had an in-between status and played important roles in mediating the relationship between the external and internal senses. If we turn to Kramer and Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum, heavily dependent as it is on Thomas Aquinas, we find an explanation of demonic manipulation through the senses in general and the phantasy in particular. Kramer and Sprenger deploy the popular form of the quasi-Aristotelian and Thomistic theory of the sensorium to explain the effects not only of delusions generated from melancholy in the phantasy, but also those directly caused by some malevolent spiritual force. Just as melancholic spirits could enter and influence the sensorium by generating false species or phantasms, so too, according to the witch-hunting pair, malevolent and benevolent spirits could enter the spirits of the brain and alter them. The point of vulnerability was either the weak external senses themselves or, and far more often referred to, the unreliable phantasy within the internal sense. As their Malleus Maleficarum puts it,

For Fancy or imagination is as it were the treasury of ideas received through the senses. And through this It happens that devils so stir up the inner perceptions, that is the power of conserving images, that they appear to be a new impression at that moment received from exterior things. (Kramer and Sprenger 50).

Here, the spirits of the brain are susceptible not only to the influence of the material of the body, but also to the influence of another form of spirit. The main point of attack for both the matter of the body but also the forces of the immaterial supernatural realm converges in the phantasy. Both the body and the spiritual realm can exploit the vulnerability of the faculty to produce delusions or illusions, making one experience something that is not there. It is this paradoxical paramaterial nature of the faculty, its spirits, and its objects that generate the potential for doubting the reliability of perception and of experience.

The Oculus Imaginationis (The Eye of the Imagination) as found on the title page of Tractatus One, Section Two, Portion Three on the Ars Memoria in Robert Fludd’s Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atqve technica historia : in duo volumina secundum cosmi differentiam diuisa (1617).

At the same time, not much separates the objects of delusion from those of actual perception. As Kramer details just before launching into his explanation of supernatural influence on the sensorium, the theory of ordinary perception relied heavily upon the central placement of the phantasy or imagination which received the impressions of objects. As they say,

It is to be noted that Aristotle (De Somno et Uigilia) assigns the cause of a[[aritions in dreams through local motion to the fact that, when an animal sleeps the blood flows to the inmost seat of the senses, from which descend motions or impressions which remain from past impressions preserved in the mind or inner perception; and these are Fancy or Imagination, which are the same thing according to S. Thomas. (Kramer and Sprenger 50).

The same structure of the sensorium explains the sequence of impressions that convert a material external object into something more immaterial that can interact with a perceiver’s immaterial soul. Sensation, perception, vivid pictures of past impressions, dreams, and delusions caused either by the natural body or by supernatural forces all made inroads within an individual perceiver through the open and vulnerable phantasy.

Horatio, who says the Ghost “…is but [Marcellus and Barnardo’s] fantasy,/ And will not let belief take hold of him” (I.i. 21-22) until he must admit that it is “something more than fantasy” (52) after he witnesses its appearance for himself, proclaims,

Before my God, I might not this believe

Without the sensible and true avouch

Of mine own eyes. (54-56).

Horatio and the soldiers maintain a distinction between the “fantasy” and perceived reality. Only Horatio’s “sensible and true avouch” of his “own eyes” can convince him of the truth of their previous report of the apparition. While the three maintain a distinction between a “fantasy” and reality, the case becomes much less clear when we explore the two in contemporary accounts of the sensorium. The phantasy was tasked with creating vain fantasies from the substances stored in the memory, but it was also responsible for the processing of ordinary perception, the very matter and source of Horatio’s “sensible and true avouch.” The matter becomes even more difficult when we also examine contemporary discourses on ghosts and spirits which also were thought to operate through the gate of the phantasy. While the three maintain a binary between the fictitious fantasy and true perception, the case might not be as clear as one might think.

Equally unstable is the distinction between matter and spirit, between bodies and souls, between appearance and illusion. While the soldiers’ “fantasies” are supposedly as substanceless as the Ghost they report, both actually are granted a material reality in contemporary accounts of the sensorium. Even the products of delusion within the faculty were granted a paradoxical nature that sat somewhere between the material and the immaterial. Neither wholly material nor wholly immaterial, neither wholly external nor wholly internally derived, the two types of species or phantasms, in their paradoxes, generate epistemological problems, but, by comparing the two, we can also see underlying similarities between them and their positions within similar early modern theories of the sensorium. It is this quasi-material aspect of both the senses and their objects that prompts me to coin the term “paramaterial,” which allows me to discuss the conflicts and contradictions embodied in early modern ontology and epistemology. While not a contemporary term, I do think it captures the paradoxes of the early modern embodied mind and helps expose the ways in which the individual perceiver was thought to engage with the world at a sensory level.

In the second Quarto, Horatio speaks a speech not found in the Folio of the same play. While of questionable authorship, the lines compare interestingly to the image of Old Hamlet Hamlet reports possessing in his mind’s eye or phantasy. When speculating about the meaning of this “portentious figure … so like the King” (106.2-106.3), Horatio calls it “a mote it is to trouble the mind’s eye” (106.5). While the Ghost has been confirmed as something more than “fantasy,” it’s persistence in the phantasy takes on a seemingly in-between nature of the Ghost itself. It is a “mote,” a substance, but a miniscule substance so small as to be close to lacking substance at all. In contrast to the vain fantasy that Horatio suspected the apparition of being, it has a quasi-substantial nature, and one that persists in the quasi-matter of the brain, its spirits. The paradoxical nature of the phantasy and its objects bridged the divide between the material and immaterial, the world and soul, the natural and the supernatural, but it was a bridge that was potentially fraught with ontological and epistemological trolls lurking just beneath. Once early moderns abandoned Galenic medicine and quasi-Aristotelian constructions of the sensorium, this bridge would be washed away for good, leaving a gulf between the world and a perceiver.

While I do think much more of a connection between a perceiver and her world was secured through theories of the paramaterial mind, there were other ways in which ontological and epistemological questions could emerge. The problem of the species or phantasms and the difficulty in determining with certainty the true from false perceptual impressions led to important ontological and epistemological questions well before the time of Descartes. Epistemological problems emerge from within these earlier (paramaterial or quasi-Aristotelian and Thomistic) systems that allows for both the possibility of actual spirits and for the persistence of phantasms in the mind that an individual can experience as being present. While Hamlet in the early portion of the play clearly does not confuse the image in his mind’s eye with actual presence and while the phantasm always-already has a subjective component, that phantasm still maintains a link—and, in some versions, I would argue a substantial link—between his mental image and the physical reality of his father. As many natural philosophers pointed out, an abundance of melancholy in the body’s “spirits” could produce experiences in which phenomena occurring entirely within the mind could be experienced as occurring without the mind.

The problem, for early modern philosophical skeptics, was that such potential for confusion emerged from a paramaterial model that implicitly or explicitly accounted the image in the phantasy as essentially the same object. A particularly vivid imagination could produce images that, when pulled from the recesses of memory, could trick the external senses into experiencing their appearance as a true report. This was supposedly especially true of melancholics who had an abundance of black bile in their substance and spirits. Speaking of the appearance of “black forms” to melancholic people, the English translation of the French physician Andre du Laurens explains that things within the eye or within the mind can be seen as if they existed without in his treatise on melancholy. He says,

The melancholike partie may see that which is within his owne braine, but under another forme, because that the spirits and blacke vapours continually passe by the sinewes, veines and arteries, from the braine unto the eye, which causeth it to see many shadowes and untrue apparitions in the aire, whereupon from the eye the formes thereof are conveyed unto the imagination, which being continualie served with the same dish, abideth continuallie in feare and terror. (Du Laurens 92).

The forms from within the brain can be taken as if they were true presences, especially in the melancholic phantasy, but this extended as well to other complexions as well. The false sights could further misinform the reasoning capacity, since reason depended upon the phantasy’s objects for its working. These types of false report could even undermine the “Captain” of the mind, reason. As the English edition has it,

The imaginative facultie doth represent and set before the intellectuall, all the objects which she hath received from the common sence, making report of whatsoever is discovered of the spies abroad: upon which reports the intellectuall or understanding part of the minde, frameth her conclusions, which are often false, the imagination making untrue reports. For as the most prudent and carfeull Captaines undertake very oft the enterprises which prove foolish and fond, and that because of false advertisement: even so reason doth often make but foolish discourses, having been misse-informed by a fayned fantasie. (Du Laurens 74).

The phantasy could trouble the proper workings of the human reason, and it was precisely because of the conflicted and paradoxical nature of the faculty and its objects that produced epistemological problems.

These natural accounts, drawing from Galenic humoralism, tend toward closing the perceiver from the world by casting mental objects with more of a subjective component and taint. It is for this reason that I, in part, contrast these relatively closed-off natural accounts with the openness of paramaterial theories by calling them perimaterial. While it is my contention that theories of a truly closed-off perceiver did not come into full emergence in the West until well after the discovery of the retinal image, I do this to contrast the medical and natural accounts which emphasized a subjective component to all perception with paramaterial ones which emphasized more of an openness to the world, both in terms of the natural and the supernatural worlds.

The epistemological problem available within this model derives from the fact that the mental phantasms or images retained an ontological connection to their originals. The memory of a particular person included sensory data and phantasms or species that mimetically reproduced external reality. While the subjective reception and response to a particular phantasm differed among perceivers, the phantasm included the attributes of its external causal agent or object, containing within it a mimetic copy of sensible reality. Despite the repeated emphasis on the conformity of mental and external objects, the phantasy still colored its phantasms with a subjective taint. As du Laurens has it, reason could be “misse-informed by a fayned fantasie,” not only when experiencing forms of things not actually present, but also in the immediate reactions to ordinary and immediate sensation of a perceptual phenomenon. Evaluations of “good and bad” and “pleasant or painful,” in many popular sixteenth century theories of perception and cognition, depended upon the “Captain,” reason, who evaluated and kept the phantasy or imagination under its control. Such evaluations could “color” perception, just as a colored lens could alter the appearance of objects or the entire phenomenological field.

Freud distinguishes mourning from melancholia based on the nature of the lost object and the extent to which mourning includes a self-loathing. In the case of ordinary grief, the distraught feelings that result from the loss of a person emerge from a subject releasing its libidinal attachment to that object. In melancholia, a similar grief emerges from a subject even if a specific object cannot be located or determined whether by the subject herself or by others. The mourner and the melancholic remain passionately attached to an object or objects, even if, in the case of a more general melancholia, that causal object cannot be identified.

If I am correct about the way sixteenth-century popular thought cast the perceptual process as something I call paramaterial, then Hamlet’s phantasm in I.ii. retains a connection to its originary cause, his father’s person. In sixteenth and early seventeenth century theories of melancholy, the melancholic “fixated” or “doted” upon a limited number of objects. As du Laurens conventionally treats in his fourth chapter, early moderns thought that “melancholike persons have all of them their particular and altogether diverse objects whereupon they dote” (Du Laurens 96). In this case, the phantasm of Hamlet’s father might literally occupy the paramaterial spirits of his brain, while at the same time retaining some connection to the physical presence of his father that was the original cause of the phantasm stored in Hamlet’s memory. I do not want to say that even in the most extreme form of the paramaterial I am sketching here that the retained phantasm was solely the product of the external object. While I do think it retained a connection to its extra-mental original in many theories, it was always-already noted that those mental objects were shaped in substantial ways by a perceiving subject.

With any perceived phenomena, the individual perceiver “colors” perception. This is true of even the most simple form of direct perception. Things become even murkier when considering memories or subjective evaluations, especially memories of something so wrapped up in personal experience like the memory of dead fathers. From a modern perspective, nothing connects the sensory system to the mental processes, but such was not the case in many pre- and early modern systems of perception. While Hamlet might idealize his father and his impressions and evaluations might be colored through his personal phantasy, in many accounts of the sensory system, something linked the perceptual apparatus to cognition. Even if much of what someone thought had a personal tinge or taint, some kernel of the real was theoretically mediated through the sensorium.

As Freud himself would argue, Hamlet idealizes his father. He seems, to Hamlet, the paragon of “man” whose death has led to the loss of the very category of “man.” It is Hamlet, significantly, who is the first to “call” the apparition his father, even if he continues to doubt and test his own perception and interpretation of the phenomena. Whereas Horatio, Barnardo, and Marcellus are more content to call the Ghost a “thing” (I.i. 19), an “apparition” (I.i. 26), “like the King” (I.i. 41) and an “illusion” (I.i. 108), Hamlet says to this “questionable shape, “I’ll call thee Hamlet,/ King, father, royal Dane” (I.iv. 25-26). While remaining skeptical of whether or not it is a true spirit, Hamlet nevertheless calls it his father, whereas Horatio remains much more skeptical of its import and significance.

Hamlet himself, who sees his father as “a man” which he “shall not look upon his like again” (I. ii. 186–187), the image in his mind’s eye continues to have a direct relationship to the man itself through the system of the sensitive soul. The phantasm of his father in his mind’s eye, or phantasy, remains connected to the phantasm stored his memory, the original of which was created by the actual person of his father. Less clear, however, is the “marvel” witnessed by Horatio, Marcellus, Barnardo and ultimately by Hamlet himself. This ghostly apparition presents an alternate side of debates on the faultiness and vulnerability of perception available to early modern theories of perception. In the play, it remains unclear whether or not an apparition appears solely to the sense or if it is either conjured by a demonic or angelic presence within the minds of the witnesses. Since the initial appearance of the ghost occurs to multiple people (and, as I shall discuss below, significantly to the audience as well), it would seem that its presence is external in origin, but the problem here is that some theorists of demonology suggested that the devil’s influence could produce mass hallucination by directly altering either the visual species presented to the external senses or by altering the phantasy of observers together in a collective hallucination.

For some, perceived angelic, demonic, or ghostly apparitions resulted from a disordered melancholic phantasy. Such explanations became standard within medical discourses from around the mid-sixteenth century onwards. Characteristic of this explanatory system was du Laurens, who argues that many of these appearances were of this order. Outside of the early modern medical tradition, however, others allow and acknowledge presences that exceed the natural as true, but often question whether those apparitions were actually the souls of the dead. The German Ludwig Lavater, in his Of Ghostes and Walking Sprites (1572), a popularly reprinted English translation that William Shakespeare might have consulted, posited that unusual specters could appear, but denied that they could ever be the actual souls of the dead. For Lavater, the phantasms were either angels or demons that took on the form or guise of the departed rather than the spirits of the dead in and of themselves. Lavater devotes a great amount of time to answering how one can determine whether a particular apparition was either demonic or angelic in nature, devotes the second part of his treatise to “discusse what manner of things they are, that is, not the souls of dead men, as some men have thought, but either good or evil Angels, or else some secrete and hid operations of God” (Lavater Author’s Epistle Sig b.ii.r). Lavater largely leaves aside the question of whether or not they have a true presence, but does argue that such apparitions are decidedly not the souls of the deceased.

Hamlet tempted to follow the ghost who looks like his father in an eighteenth century engraving.

Cautioning against malicious devils who assume a pleasing shape to delude and tempt observers, Lavater states that the only real way to know if a spirit is good or bad is to consider the nature of their requests. Lavater applies first John to the realm of ghosts and spirits, saying,

Saint John saith in hys first Epistle and fourth chapter: Dearly beeloved, beleeve not every spirit, but trie the spirits whether they are of God: for many false Prophetes are gone out into the world. Heereby shall yee knowe the spirit of God. Every spirit that confesseth yt Jesus Christ is come in the flesh, is of God, and every spirite whiche confesseth not, that Jesus Chryst is come in the flesh, is not of God, etc. Heere he speaketh not of spirites which falsly affirme themselves to be mens soules, but of those teachers whiche boaste of themselves that they have the spirite of God. But in case we must not beeeve them being alive, much lesse ought we to credite them when they are dead. (Lavater 203).

In addition to speaking correctly of God, a good angel will request positive actions from an observer while evil spirits will request the performance of evil deeds. Old Hamlet’s demand for vengeance, from something like Lavater’s standpoint, would tend towards the demonic. From such a vantage point, the ghost’s demand for revenge serves as an even more effective way to damn Hamlet’s soul by encouraging blood vengeance against his uncle than in “tempt[ing him] toward the flood” (I.iv. 50) in the way Horatio warns Hamlet against. Shakespeare provides very little clarification of the matter by only allowing Old Hamlet to speak directly to Hamlet, without the confirming observation and experience of witnesses.

Since the only time the ghost appears again onstage with a potential witness is during the closet scene where Hamlet speaks “with th’ incorporal air” (III.iv. 109), Gertrude can neither see nor hear it, the exact nature of the ghost remains ambiguous and complicated. If the initial appearance was a mass delusion of the order discussed in witchcraft discourses, either Gertrude is hindered from receiving the sensible species of the apparition, or Hamlet’s encounter occurs, like the earlier image of his father in “his mind’s eye,” only in the phantasy. This is, of course, not to say that Hamlet is necessarily delusional here, but the ambiguity involved here does expose the problems inherent in the role of the phantasy in sixteenth century constructions and the way that those problems could generate skeptical potential.

II. “Is not this something more than fantasy”: The Epistemological and Skeptical Potential of Paramaterial Phantasms

Classical Stoics had attempted to ensure the certainty and reliability of ordinary perception by creating two distinct types of perceptual phenomenon, cataleptic and acataleptic. The first, cataleptic perception, accounted for perception that occurred in the presence of an external object, while the second, acatleptic perception, accounted for perceptual phenomena occurring in the absence of an external object. For the Stoics, delusions fell into the category of acaleptic impressions, which being considered distinct from cataleptic impressions, did not question the reliability of perception or the knowledge available through the senses. Instead, reason could recognize and account for their divergence from supposed reality. Skeptics, however, challenged the separation; arguing that, in essence, all perception is acataleptic, or, at best, could not be entirely distinct from cataleptic ones. Skeptics like Sextus Empiricus could argue that since there was not an external judge of the matter, one needed to suspend judgment.

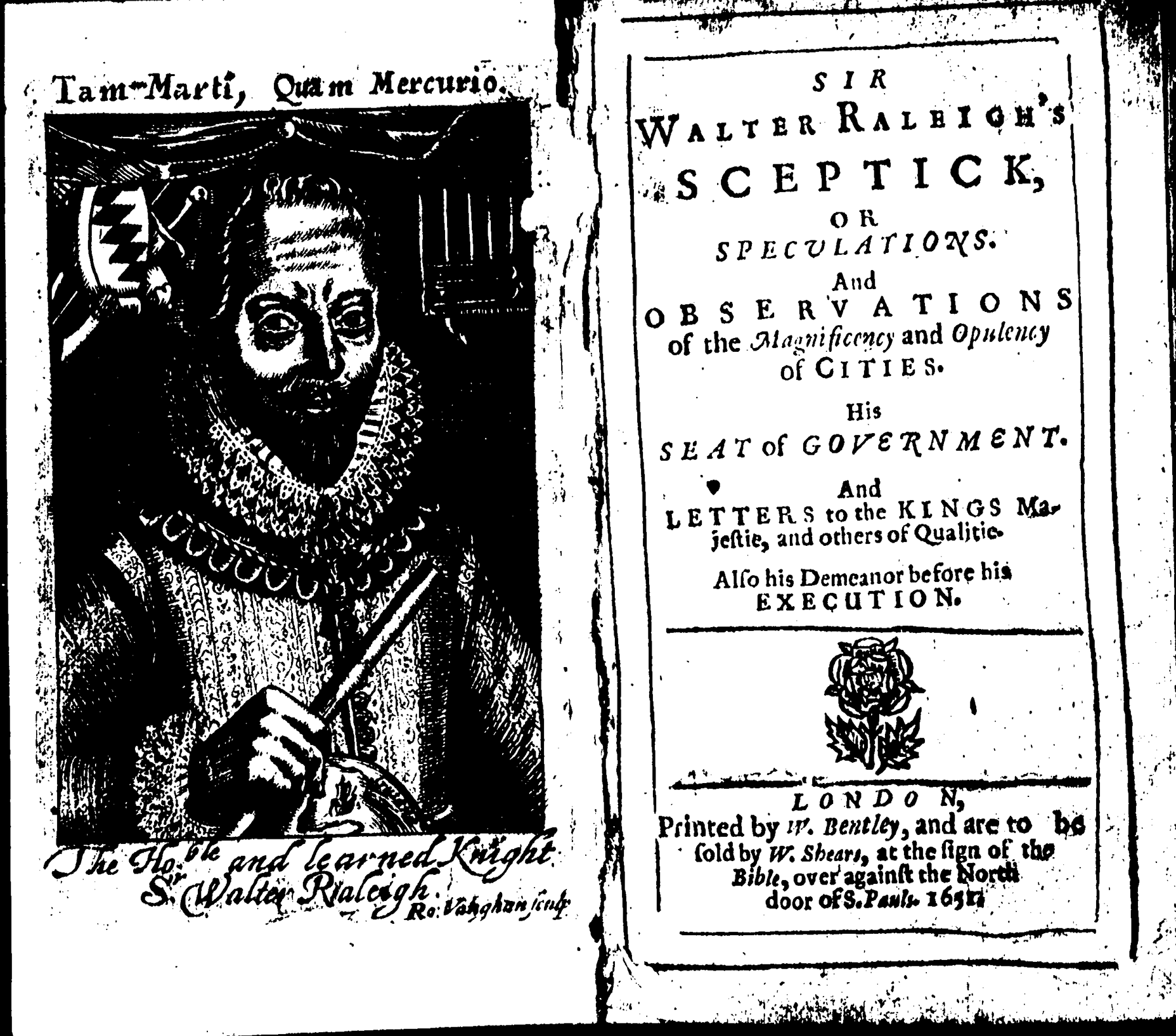

In an early modern expurgated English translation and adaptation of Sextus Empiricus, sometimes attributed to Sir Walter Ralegh alone, the phantasy becomes a central focal point for skeptical questions and questioning. While not stating it directly, the phantasy comes to play a central role in many of the aberrant perceptions that help unsettle the certainty available to humans through the senses. While Sextus and Ralegh’s adaptation, the Sceptick, never mention supernatural manipulation, it does draw from Galenic medicine to undermine the reliability of ordinary perception. Again, melancholy becomes the main culprit.

Title page detail from Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy.

Melancholy was the humor traditionally associated with madmen. Capable of producing delusions and hallucinations, when in over-abundance, the humor was a dangerous one even with its positive associations with genius, literary or otherwise. For skeptics, the type of melancholic delusion undermined the reliability of the senses precisely because there was not an objective and impartial way to determine which impression was correct. Stoics attempted to use melancholy to separate cataleptic from acataleptic impressions, likening delusions to powerful imaginings of absent objects. For skeptics, rather than solidifying a strict binary opposition between ordinary and aberrant perception, the moments of recognizable failure or diversity of opinions on a particular matter of dispute question the reliability of perception and judgment in its presumed “normal” state. As Raleigh puts it,

If then it be so, that there be such differences in Men, this must be by reason of the divers temperatures they have, and divers disposition of their conceit and imagination; for, if one hate, and another love the very same thing, it must be that their phantasies differ, else all would love it, or all would hate it. These Men then, may tell how these things seem to them good, or bad; but what they are in their own Nature they cannot tell. (Raleigh 23-24).

The “diverse temperatures” and “divers disposition[s] of their conceit[s] and imagination[s],” produce different impressions, but, unlike the Stoics or other “Dogmatiques,” this does not give a basis for providing a way to determine the relative truth of one over the other for the skeptic. Instead, the variation compels questions about the reliability of all perception. Because of this, the skeptic is not led to a judgment apart from knowing the limitations of his own position, leaving the skeptic with only a “report” rather than “truth.” As Raleigh’s Sceptick concludes, “I may then report, how these things appear, but whether they are so indeed, I know not” (Raleigh 31). Whereas the Stoics tried to clearly distinguish cataleptic and acataleptic impressions, the skeptics saw no such clear separation. Instead, nearly all sensory information was potentially acataleptic in nature, and that it was therefore necessary to suspend judgment on the certainty available through them.

Ralegh’s Sceptick begins by probing what it sees as a false dichotomy between human and non-human animals. For the text, as it was for Sextus’ Outlines from which much of the Sceptick is lifted, the form and natures of the external senses, their “temperatures” of various forms of sentient life, and the condition and quality of their internal senses, produce different impressions that the phantasy or imagination received and upon which reason and judgment depended. As the Sceptick puts it,

if the instruments of Sence in the body be observed … we shall find … that as these instruments are affected and disposed, so doth the Imagination conceit (sic) that which by them is connexed unto it. (Raleigh 3–4).

For this text and for Sextus’ Outlines before it, the external senses were vulnerable to misapprehension which could shape the impression offered to the phantasy, since “according to the diversitie of the eye … offereth it unto the phantasie” (Raleigh 6), but so too could the phantasy alter the impressions of its own accord, depending upon the temperament of the perceiver as well as upon the related quality and condition of the spirits filling the brain. Both the external and the internal senses could alter the forms which they received, and both were locked in a mutual embrace of sense shaping, especially at the point of their meeting in the faculty of the imagination or the phantasy. Both exerted a shaping influence on the species or phantasms originating in the forms of external objects, and both could generate and support skeptical arguments about the nature of reality and of the availability of certatinty.

While classical to sixteenth-century philosophical skeptics rarely mention the delusions caused by the devil, they too contain skeptical potential. Within the discourses of demonic influence, the skeptical logic could follow suit. This is precisely the logic involved in seventeenth-century French polymath, Rene Descartes, followed when he developed his thought experiment of the evil demon. As Descartes has it,

I will suppose therefore that not God, who is supremely good and the source of truth, but rather some malicious demon of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies in order to deceive me. I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely delusions of dreams which he has devised to ensnare my judgement. I shall consider myself as not having hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses, but as falsely believing that I have all these things. I shall stubbornly and firmly persist in this meditation; and, even if it is not in my power to know any truth, I shall at least do what is in my power, that is, resolutely guard against assenting to any falsehoods, so that the deceiver, howsoever powerful and cunning he may be, will be unable to impose on me in the slightest degree. But this is an arduous undertaking, and a kind of laziness brings me back to normal life. I am like a prisoner who is enjoying an imaginary freedom while asleep; as he begins to suspect that he is asleep, he dreads being woken up, and goes along with the pleasant illusion as long as he can. In the same way, I happily slide back into my old opinions and dread being shaken from them, for fear that my peaceful sleep may be followed by hard labour when I wake, and that I shall have to toil not in the light, but amid the inextricable darkness of the problems I have now raised. (Rene Descartes Translated by Cottingham 79).

Though I am not aware of direct earlier English skeptical texts which deal with demonic delusion, the instances of it provide potential for skeptical questions and concerns. If the natural could influence and shape sense in such a way as to undermine the certainty of perception and judgment, so too could the belief that the devil or his forces could also shape sense. Descartes’ evil demon thought experiment draws such conclusions to an extreme point, and Descartes therefore makes more explicit the skeptical potential already encoded in representations and discussions of demonic deception and illusion.

The Frontispiece to the 1620 edition of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus.

Descartes’ evil demon has foundations in the discourses of the previous century. In the mid-sixteenth century, the Swiss physician Johann Weyer offered a Galenic account of the delusions commonly associated with demons, devils, and witches. For Weyer, nearly all forms of such delusion resulted from an overabundance of melancholy in the body and especially in the spirits of the brain. The most “vulnerable to the demons’ arts and illusions,” were the melancholics. Of the most likely to be attacks,

Melancholics are of this sort, as are persons distressed because of loss or for any other reason, as Chrysostom says: “The magnitude of their grief is more potent for harm than all the activities of the Devil, because all whom a demon overcomes, he overcomes through grief.” (Weyer 180).

While never denying the existence of demonic forces in the world, Weyer did provide an explanatory system that allowed for readings of some forms of delusion typically attributed to Witches and demonic forces to natural causes. The idea was not a particularly new idea even if the scope of his arguments included many forms of aberrant perception that for others fell under the purview of witchcraft and demonology. Weyer goes on to describe the devil’s powers over the body in terms that are not all that dissimilar from the ways in which Kramer and Sprenger describe them. Weyer details that a devil

…may assume some attractive form, or variously agitate and corrupt the thoughts and the imagination, until finally these people agree with his proposals, give way to his persuasion, and believe whatever he puts into their minds, as though bound by treaty—depending on his will and obeying him. They think that everything that he suggests is true, and they are devoutly confident that all the forms imposed by him upon their powers of imagination and fantasy exist truly and ‘substantially’ [in the theological sense] (if I may use this word). Indeed, they cannot do otherwise, since from the time of their first assent he has corrupted their mind with empty images, lulling or stirring to this task the bodily humors and spirits, so that in the way he introduces certain specious appearances into the appropriate organs, just as if they were occurring truly and externally; and he does this not only when people sleep, but also when they are awake. In this manner, certain things are thought to exist or to take place outside of the individual, which in fact are not real and do not take place, and often do not even exist in the natural world. (Weyer 181).

Weyer offers a more natural and material account of the delusions of devils, but also exposes the vulnerabilities to which early moderns attributed to the paradoxical phantasy. Even witch hunters Kramer and Sprenger acknowledged the possibility that natural causes resulted in some of the perceived phenomena, but part of their task was to separate the false from those of true demonic influence.

The most critical of demonic visions in the period was the English Reginald Scot, who, like and following Weyer saw most “demonic influence” as the effect of melancholy on the phantasy. Countering demonologist and theologian Jean Bodin for his attack on Weyer, Scot states,

But bicause I am no physician, I will set a physician to him; namely Erastus, who hath these words, to wit, that these witches, through their corrupt phantasie abounding with melancholike humors, by reason of their old age, doo dreame and imagine they hurt those things which they neither could nor doo hurt; and so thinke they knowe an art, which they neither have learned nor yet understand. (Scot 33).

Though he discusses the delusions of witches in particular in the above, the same holds for the melancholic visions of the dead and of other supposedly supernatural occurrences according to Scot. Though even more extreme than Weyer, Scot too never fully denies the presence and influence of the occult and the spiritual altogether. He, too, acknowledges their influence even if he, like Weyer, was condemned by James Stuart for supposedly doing so. The spiritual influence upon perception and upon thought, even for a skeptical challenger like Scot, was taken for granted in popular vernacular treatises. Though melancholic influence could explain many cases, it was not an exhaustive explanatory system. Even by the time of Robert Burton in the 1620s, explanations of the senses and of melancholy referred to demonic influence. All remain linked to discussions of the “reality” of spectral presences.

In this way, the lack of certainty regarding the nature and significance of Old Hamlet in the opening scene of Shakespeare’s play takes on new importance and significance. The play opens with questions about the nature and meaning of the ghost. The anxiety and uncertainty of the Danish state relates to the anxiety and uncertainty generated by the ghost’s appearance. Something is, after all, rotten in the state of Denmark. Lavater, who claims that true spirits cannot return from the grave, also conjoins anxieties over politics and the appearance of specters when he claims that phantasms who appear dressed in full armor actually speak to alterations of the state and political turmoil. Lavater notes that in

… the Court of Mattheus, surnamed the great Sheriff of the City, in the Evening after sun set, there was seen a man far exceeding common stature, sitting on a horse in complete amour: who when he had been there seen of many, by the space of an hour, in the end vanished away to the great terror of those that beheld him… Not long after, Henry the seventh Emperor, departed this life, to the utter undoing of all the Sheriffs.” (Lavater 68).

According to Lavater, armed apparitions foretell of turmoil within and alterations of state. Something is rotten in Denmark as it is under present threat of attack by Fortinbras’ army, who seems to have set his sights on Claudius to test his power thinking that Claudius’ “state to be disjoint and out of frame” (I.ii. 20), even as the former ruler’s spirit seemingly rises from his rotten and rotting body. Horatio, initially skeptical that the ghost even exists, wonders, without stating his queries in such terms, whether its appearance constitutes an acataleptic impression, existing only within the heads and minds of Barnardo and Marcellus.

Such issues are not necessarily new, being one of the most popular undergraduate discussion topics for seemingly as long as there have been Shakespeare courses, but framing the issue through a discussion of early modern theories of the sensorium brings to light how the two phenomena were related and similarly conceived and constructed in the period. While it cannot answer whether the ghost is true or false, a true spirit or a devil, or if it is a product of Hamlet’s madness, examining the theory of the senses allows us to see a range of responses available within the period. This framework allows us to see the multitude of ways in which this theory of the senses generated the potential for early modern skepticism well before Descartes, even if Descartes explicitly addressed and amplified their skeptical potential. Additionally, these issues bring into relief problems inherent in the nature of the stage itself in earlier theories of perception, and sheds light on some of the Protestant fears and anxieties regarding the potential of fictions in general and of the stage in particular.

Even if Lavater might not be a direct “source” of Hamlet in a traditional sense, an early modern audience member familiar with the popular Of Ghostes and Spirites Walking by Night (1572) would have a sense that all might not turn out well for the Danish power by the play’s end. Such a reading might have an even broader base even for those unfamiliar with Lavater directly, but, in any case, Lavater shows us how readily the idea of spirits and the threats to or alterations of the state are linked within the popular imagination. Even if the ghost is read as a malicious devil lacking the true substance of the murdered monarch, it still might represent a harbinger of such problems and alterations of the Danish state.

Skeptical in his own right and possibly conforming to the Stoic distinction between cataleptic and acataleptic impressions, Horatio, it seems, demands confirmation as to whether or not Marcellus and Barnardo suffer from an acataleptic impression of the dead king, but even when his own experience proves it true, his skepticism extends to precisely what the apparition is supposed to mean. Even if they collectively confirm the presence of something “like” the dead king, the meaning of the its appearance can mean a variety of things. It may, for example, still be the deceiving demon that Horatio later cautions Hamlet against. Having proved through personal experience and having confirmed through collective experience that something is present, Horatio, like, to a lesser extent, Hamlet, must determine the origins and meaning of its appearance. His seemingly Stoic sensibilities and his non-philosophical skepticism creates a situation where he is never fully assured of the ghost’s meaning that he personally witnesses. Like Lavater, too, he tends to doubt the actual presence of the dead monarch while simultaneously holding open the very real possibility that it is some sort of qenuine quasi-physical vision which he leaves to Hamlet to determine.

It is tempting to think that the apparition witnessed by so many parties in the first scene of the play foretells of an alteration of the state in a similar way. Old Hamlet’s Ghost, similarly armed in full armor, might be the harbinger of a time of great political unrest and disquiet, and, might, even reveal the ultimate transfer of power to Fortinbras. This is neither to say that Shakespeare read Lavater, though it is likely Shakespeare knew of him, nor to suggest that Shakespeare would have necessarily held the same views even if he had read Lavater, but it is intriguing to consider that the play poses both issues in conjunction and contention within its opening salvo, issues that will never fully be resolved even by the play’s end. The ghost’s appearance leads to the “utter undoing” of Denmark’s ruling order, ultimately transferring power from traditional Danish royalty to Fortinbras, a foreign authority and power.

An illustration of Hamlet and the Ghost from the verse “Hamlet: The Comic Song.”

For someone of Lavater’s persuasion, a spirit in full armor represents an omen of an impending alteration of state. In Shakespeare’s play, the status of the ghost remains unclear, but its appearance both shows that there is something rotten in the state of Denmark and helps precipitate the alteration of state in the form of Fortinbras’ ultimate assumption of the throne. Noting the parallels between Lavater’s take and Shakespeare’s play does not necessarily resolve whether or not the spirit is either the actual spirit of Old Hamlet or if it is a demon assuming the guise of Old Hamlet, but it does allow us to feel the presence of the supernatural in the world of the play. As with Macbeth, the issue remains open as to whether the apparition, like the witches, help cause the events or if they merely foretell of their coming. While I am not trying to say that a stance like Lavater’s is the only conclusion or that Shakespeare directly draws from Lavater, I do think such a reading would have been available to some within Hamlet’s original audience.

Several readings, presumably, would have been available to a contemporary audience, existing simultaneously within the realm of interpretive possibility. The first, those that who accepted without question the existence of true ghosts and spirits like Kramer and Sprenger or James Stuart could see the Ghost as the true form of the dead ruler. The second, those that acknowledge the possibility of marvelous sights and visions, like Lavater, could see the political significance of the armed spirit’s appearance while denying the possibility that they are true spirits or souls of the dead. The third, those who attributed most aberrant perception to natural causes and to melancholy like Weyer or Scot, could see the apparition as the projection of disordered and melancholic bodies and minds. All of these types, including the last, however, typically acknowledge the possible real influence of benevolent or malicious spirits even as they disagreed about the extent to which those entities could shape sense and what those appearances meant, and, though I have separated them into distinct types here, they often blend and merge with one another.

As I said previously, the natural explanations of those like Weyer and Scot tend towards what I call a perimaterial order which closes some of the connections available between a perceiver and her world. Kramer, Sprenger, and James all leave open the full paramaterial possibility that the supernatural world can inform and influence either the world or perception. As I said before, however, even the most extremely natural in their explanations of aberrant perception, prior, at the very least, to the seventeenth century, still often saw the perceptual process, in ordinary perception, as remaining open and positioned somewhere between the material and immaterial; a place that I continue to call the paramaterial. If we look back at the description of the Devil’s powers in Weyer that I cited previously, his explanatory system is not all that different from those found in Kramer and Sprenger even as the scope of his natural explanations are much broader.

In spite of this, James Stuart still famously referred to both Weyer and Scot as proclaiming a Sadducceanism, denying the realm of the spiritual and the soul altogether. While those like James Stuart mischaracterized Weyer and Scot, very few even by the late sixteenth century openly held such an extreme position and accounted for all such phenomena through Galenic medicine. This is not to say such a position was entirely unavailable, but was much more uncommon than it would seem if one was only familiar with critics of natural approaches like King James. While not exhaustive, these three types of reader constitute what I find to be the most common early modern responses to witchcraft phenomena. I have yet to find someone who explicitly denies the influence of the supernatural altogether in the way that James suggests. Though Reginald Scot comes the closest, the response to his Discoverie shows how dangerous such outright denials would have been as well as to show the limits of skeptical questions regarding supernatural influences.

On the naïve level, those who accept the ghost as the true spirit of the dead king can see the play, as Hamlet does, as a simple tale of revenge prompted and sanctioned by Heaven and Hell. Such a view, while naively accepting the presence of the fictional ghost, allows for an extreme form of paramateriality in which natural and supernatural realms interact and merge within the perceived world. For those more skeptical of supernatural influence, they could see the appearance of a form like the dead king as a sign of Hamlet’s melancholically produced delusion; a projection of his sunburned brain upon the political and familial situation. In this, an astute reader must acknowledge that the form visible to others in I.i. has an existence independent of Hamlet’s mind, yet, they can still question the reality of the experience of the speaking spirit that confirms for Hamlet his “prophetic soul.” As such, however, the initial appearance to others might simply mean, as Lavater says of his armed spirit, that change is coming to the ruling order. In both types of reading, natural explanations might explain the spirit that speaks to Hamlet directly. In accordance with this natural account and more perimaterial reading of the ghost’s subsequent appearance and conference with the titular character, the ghost becomes a phantasmal projection of Hamlet’s interior phantasm. The “man” Hamlet reports seeing in his “mind’s eye” in I.ii. is made manifest on the stage. As such, Hamlet’s supposed internal vision becomes physical as the actor playing the Ghost offers its own “impressions” on the external and internal senses of the audience.

The speaking spirit Hamlet later encounters, for most purposes, should be bracketed off from the visible spirit of act I.i.. As is well known, while the visible apparition has multiple confirming witnesses, the spirit that speaks only does so to the character of Hamlet. Since Gertrude does not perceive the spirit during the closet scene, it calls into question whether the speaking spirit Hamlet encounters and converses with previously, and we can never be sure if it constitutes either an externally or internally constructed phantasm. For physicians like Johann Weyer, many witchcraft phenomena emerge from melancholic matter within the spirits of the brain, which cause the perceiver to experience that which is within as if it came from without. The self-identifying and self-reporting melancholic prince may experience such events without their actually being present.

III. “Who’s there?”: Performing Phantasms Complicating matters even further, however, is that the audience does experience the ghost’s words both in the earlier scene and in the later closet scene. The situation in Hamlet differs dramatically from Macbeth’s encounter with the dagger which, depending upon the production, either chooses to display a visible dagger to its audience or to rely solely upon Macbeth’s self-report. With Macbeth, the dagger scene either confirms that a supernatural presence propels the eponymous character towards action or reveals Macbeth’s possibly delusional private phantasy. The audience’s understanding can be pushed in either direction depending upon whether or not the director chooses to display a visible dagger or not. In Hamlet, we encounter the ghost along with the other characters, even when someone like Gertrude within the world of the play cannot. For us, the physical presence of the actor upon the stage creates a disjunction in which the audience is either pulled into Hamlet’s private experience or which confirms the supernatural reality of the ghost’s real presence.

The Ghost Scene performed on stage.

Again, this fact does not help us resolve the central problem of whether or not the apparition is either the spirit of the dead king, if it is a demon in disguise, or if the speaking spirit is supposed to be the psychomachic projection of Hamlet’s melancholic brain, but, had Shakespeare not included the Ghost’s dialogue, a director could more easily decide to either highlight Hamlet’s emergent madness by not staging the ghost’s physical presence or more strongly confirm our link to the central character by showing him to us. Instead, Shakespeare provides a phantasm that speaks which must—at least if they decide to preserve the lines—impress a physical presence upon the audience. Even if we speculate that Hamlet talks to the incorporeal air, we are provided some form of physical presence. We, in essence, share the same perceptual field with Hamlet, encountering both the visual and auditory impressions the actor playing the ghost provides us.

The melancholic Prince might not be above the level of hallucination since the black bile was the one most related to aberrant phenomenal experience and delusion. As Lavater says,

…it can not be denied, but that some men which either by dispositions of nature, or for that they have sustained great misery, are now become heavy and full of melancholy, imagine many times with themselves being alone, miraculous and strange things. Sometimes they affirm in great soothe, that they verily hear and see this or that thing, which notwithstanding neither they nor yet any other man did once see or hear. (Lavater 10).

Many late medieval and early modern physicians would agree. For example, Du Laurens speaks of melancholics similarly, claiming that melancholy generates false perception and sensory experience. He says,

The melancholike partie may see that which is within his owne braine, but under another forme, because that the spirits and blacke vapours continually passe by the sinewes, veines and arteries, from the braine unto the eye, which causeth it to see many shadowes and untrue apparitions in the aire, whereupon from the eye the formes thereof are conveyed unto the imagination, which being continualie served with the same dish, abideth continuallie in feare and terror. (Du Laurens 92).

From such a position, the material or natural account, or perimaterial reading, could argue that apart from the more broadly visible spirit of the early scenes, that he ghost is a product of Hamlet’s melancholy. The image of his father, in the spirits of his brain, become, for him as for the audience, a visible and auditory reality. Hamlet, who “dotes” upon the image of his dead father and whose “prophetic soul” already suspects his uncle for murder, may be feeding his own fear and terror with a projection from his phantasy. Such a position places the philosophical skeptic in a situation where all of sensible reality might seem little more than a phantasm or an imagination. If melancholy can produce delusions of reality from the depths of the brain, what is to secure the reality of any perception?

Humoral theories held sway well into and sometimes past the seventeenth century, but, in each, the presence of an abundance of melancholy in the spirits of the brain, and especially its presence in the phantasy could produce delusions and hallucinations. While we cannot say definitively whether Hamlet suffers from demonically inspired delusions or that he suffers from melancholic hallucinations, he does report that the image of his dead father is an object upon which he fixates or “dotes.” Humoralism was still current even by the time of Burton in the early seventeenth century in both natural and supernatural forms, the paramaterial and the tending-towards-the-perimaterial. While a majority of his Anatomy of Melancholy describes the material, natural, and non-natural causes and effects of melancholy on perception and upon thought, he also includes sections on supernatural causes of melancholy. Burton will not settle whether they have mostly material causes, but he does expose how melancholy and witchcraft merge in the popular imagination when he says,

Agrippa and Lavater are persuaded that this humour invites the devil to it, wheresoever it is in extremity, and, of all other, melancholy persons are most subject to diabolical temptations and illusions, and most apt to entertain them, and the devil best able to work upon them. But whether by obsession, or possession, or otherwise, I will not determine. (Burton Pt I. 200-201).

This blended explanation was the most common form not only in the seventeenth century but also in the sixteenth century. Neither fully subscribing to a fully material explanation, nor willing to allow for many supernatural causes, Burton and others often left the possibility open for each.

Similar issues emerge at the intersection of natural and supernatural causes of aberrant perception. The two attempt to explain phenomena attributed to devils and witches, but both explain an aspect of perception that calls into question the reliability of ordinary perception and experience. The two compete for dominance, but, it should be remembered that even the material accounts sound “modern,” they are decidedly not so. The natural or material readings are not perimaterial to the extent of modern understandings of perception and of the sensorium. Instead, they emerge out of Galenic medicine and a paramaterial model of the mind which continues to stress the relationship between external objects and a perceiver, despite the crises of sense available from within these earlier models. It was not, I contend, until the full collapse of the Galenic and Aristotelian conceptual orders, along with the discovery of the retinal image that ushered in a modern understanding of the subject and more modern perimaterial forms of perception and thought. It was an overall shift away from a shaping of sense and more towards a modern making of sense.

Though we can never provide a single answer to the questions around the margins of what the issue of the real presence of Old Hamlet means, we can explore how the different available possibilities might have appeared to different types of early modern audience members. In this, I somewhat follow the interpretive framework sketched by Gareth Roberts in an article on Doctor Faustus, “Marlowe and the metaphysics of magicians.” There, Roberts argues that three forms of discourse on witchcraft can be found in Marlowe’s play and within early modern culture at large. Roberts offers orthodox magic, high magic, and popular belief as interpretive frameworks, but I would like to frame my discussion through a triangulation of authors on ghosts and aberrant perception rather than through three different distinct types. To me, framing the issue through Kramer and Sprenger, Lavater, and Reginald Scot provides a useful triangulation through which to view range of responses to how theories of perception intersect with the notions of spirits and ghosts. Rather than just embodying three distinct types of theory of magic, these three groups of authors, to me, embody a spectrum of paramaterial theories of perception that are variously more open to external influence to the more closed and insular, and those that are open to supernatural causes and those that are more limited to natural accounts.

If we do not take the ghost as true, we are potentially engaged, therefore, in either a melancholic or a demonic vision along with Hamlet. The stage and the actors which occupy it provide us with a certain sensory experience, but, as with the ghost, our collective experience does not settle what such a phenomenon might mean. The actors themselves, like the potentially demonic spirit, assume and present forms that are not their own. Like the spirit of I.i., the actors offer a phenomenal reality complete with externally assured confirmation, but, as with the spirit, we neither know what those phantasms mean nor whether we should trust the appearances they present. In fact, at an important level, we know that the stage offers only an appearance or deception, but it one that is crafted to deceive. Such a fact does not necessarily equate the stage and its actors to deceiving devils, but it does open up the possibility.

Hamlet encounters the Ghost.

Since the devil, according to people like Lavater, assume forms that are not their own in order to deceive and trick their perceivers into either thinking or acting differently, the stage has the potential to do likewise. The physical presence of the actors offer sensible species of reality, but the illusion offered in the context of the theater shapes that into the phantasm of a character. The actors both are and are not themselves and are and are not their characters. The physical presence of the stage ensures that the phantasms have more of a unified aspect in the phantasies of their observers and auditors than with the phantasms constructed in the minds of those reading a book. For those reading about rather than experiencing the physical presence of another pulls fragments of others and things from the memory, reassembling and recombining them into the figure of a specific character, but an actor gives off sensible species that “impress” themselves on spectators. The character becomes linked in this way to a bodily presence, providing the phantasy with a phantasm that is both a true and a false phantasm. The ambiguous phantasm offered in the theater finds parity in the initial appearance of the spirit in Hamlet. The potentially deceptive nature of the ghost exposes the potential for the demonic nature of the theater.

Even more strange, however, is that we more readily accept the presence and existence of the phantasm of Old Hamlet when we hear Hamlet’s report in I.ii. than we do of his deceased father elsewhere in the play. Hamlet’s self-report of the phantasm in I.ii. is entirely fictional and illusory; one that has no existence whatsoever. The actor playing Hamlet does not, unless he is legitimately mad or a very great method actor, have a phantasm of Old Hamlet present in his phantasy while he reports its presence. Unlike the “Ghost” we see and experience, we, as audience members, never receive a species or phantasm confirming its presence in the spirits of Hamlet’s mind. We take it at face value and as a genuine and true presence despite its noted absence. The mind behind the actor that we experience is entirely illusory in the way we experience it. Hamlet’s mind is the projection of depth from an illusory surface. In this way, the play gives us more cause to accept the reality of the supernatural than it does in the acceptance of other minds.

The actor may, like the audience by this point, imagine the phantasm of the actor who plays the Ghost within his mind. In doing so, we create a phantasm of a character who is never fully present—much like the phantasm that appears to the soldier in the first scene of Hamlet. The character is only a phantasmal projection which has no existence apart from the “spiritual” form we encounter along with other characters in I.i. The actor has a substantial reality, of course, but the character he plays is a pure phantasm. As with all imaginings of a fictional work, the phantasms are shaped through their context and depend upon and build from physical experiences whether present or those retained from the past. Watching an actor upon the stage, we have the sensible species of the actor, but, when reading, we construct that phantasm from parts already stored within the memory.

What separates our contemporary understanding from the sixteenth century’s understanding of spectatorship, however, is that sensory and perceptual phenomena—the sensible species and their mental equivalents sometimes referred to as phantasms—are, to some extent, theoretically preserved in the matter of the brain, and served as the basis from which thought and subsequent imaginings emerge. The mimetic qualities of the phantasy ensure, where cataleptic impressions are concerned, the relationship of external and internal objects. While “colored,” distorted, complicated, or complimented by the subject experiencing them, the mimetic nature of the sensitive soul preserves some kind of relationship between extra- and intra-mental objects through their persistence in the very matter of the brain. While supplemented with subjective evaluations, the system explains the relationship of external and mental objects through their retention and preservation in the mind. One would imagine that such a system would preclude the extreme skepticism found later in thinkers like Descartes, but the system had complicating factors which raised similar issues and generated epistemological problems.

We often approach the early modern from the position of the modern, and often do so from a perimaterial perspective which developed, I argue, in the early seventeenth century. While I do not find Descartes solely responsible for this turn, he is positioned at a key moment where skepticism and newer optical theories converge. While Descartes countered skepticism he offered skepticism in an extreme form before doing so. Part of what allowed for the radical skepticism that Descartes goes on to try to defeat, I argue, is the discovery of the retinal image and its inversion, but he did articulate a form of philosophical skepticism that radically expands its epistemological horizons even if he develops tropes from earlier expressions of skepticism. Even later, another philosopher interested in optics and in defeating philosophical skepticism, Bishop George Berkeley, would counter this new all-encompassing type of philosophical skepticism by developing his Idealism. In the eighteenth century, Berkeley would offer, in his Idealism, an interesting parallel to Descartes’ evil demon. Instead of offering a thought experiment about universal deception at the hands of an evil demon, Berkeley offered what could be thought of as a universal illusion at the hands of God. In this sense, Berkeley offers phenomenal reality as a type of divine illusion in contrast to Descartes’ malicious devil which creates universal delusion. Whereas Descartes offers the possibility that a devil might delude us into taking a false phenomenal reality as a true one, Berkeley suggests that phenomenal reality might be a type of illusion structured and sustained by the godhead. Whereas Descartes develops and expands skeptical tropes available in the world of the pre-retinal image, Berkeley’s response, I believe, depends upon this new construction of the senses. While the Berkelean Idealism found later might be unavailable in this previous model, these previous models did often expose the faultiness of the phantasy and its objects. In these earlier models of the sensorium and the sensitive soul—at least in many vulgar formulations—the fact that the body could produce acataleptic impressions that emerged from humoral imbalances and the possibility that angels or demons could alter the perception of perceivers posed serious epistemological challenges and problems. The extremist form of those concerns emerge in the work of Descartes, but the problems of epistemology Descartes formulates in the Meditations are imperfectly mirrored in these earlier constructions.

When Descartes questions the sensible reality of his own body including the existence of his hands, he tellingly says,

Again, how could it be denied that these hands or this whole body are mine? Unless perhaps I were to liken myself to madmen, whose brains are so damaged by persistent vapours of melancholia that they firmly maintain they are kings when they are paupers, or say they are dressed in purple when they are naked, or that their heads are made of earthenware, or that they are pumpkins, or made of glass.” (Descartes 77).

Here, Descartes compares his skeptical assault on epistemology and ontology to the common motifs of the melancholic and delusional. He goes on to offer an extreme form of skepticism, including the Cartesian demon, that does doubt the existence of reality, effectively challenging any distinction that could be made between the sane and the mad, but this passage also reveals just how much skepticism, even after the discovery of the retinal image, depended upon the motifs and terms of Galenic medicine.

On the one hand, the delusions of “madmen” challenge the certainty of perception, and, on the other, an evil demon could be producing false phenomena that people experience as true reality. All of experience might, from Descartes’ exaggerated thought experiment, proceed from a devil which creates the illusion of sensible reality. Descartes’ evil demon, however, only constitutes an extreme form of the epistemological concerns already present in sixteenth century culture. The problems posed by a system that needed to acknowledge the influence of angels and demons upon sensation and upon material reality always-already contained the threat to the certainty available through perception.

Descartes’ evil demon, though he is more radically expansive in his thought experiment, exaggerates the fears and anxieties already contained within debates concerning the devil’s ability to manipulate perception and experience. This exaggerated form, however, explicitly exposes the skeptical questioning of the reliability of all human perception. Preceding Descartes, the fact that the devil could create false phantasms and phenomena expose the unreliability of perception, even if those questions were not framed as the devil’s ability to completely fabricate the whole of perceptual reality. As with Old Hamlet’s ghost, Macbeth’s dagger, and Faustus’ displays of skill, the fact that the devil could produce or shape appearance, species, and phantasms, opened the possibility that anything experienced could, in fact, not conform to reality or may be a demonically inspired delusion.

Those approaching delusion from the medical tradition, however, also undermined the reliability of perception, since the humoral condition and disposition of a perceiver might distort, or might even fabricate reality from yet another direction. Such accounts not only challenged theological discussions of spiritual influences, but also highlight the problems inherent in a system that saw more continuity between mind and body. The medical tradition provided a mechanistic hypothesis for aberrant perception and for cases of demonic manipulation. In this, there was the potential to clash with theological explanations, but this mechanistic model similarly undermined the certainty of perception. Again, this side of skepticism resurfaces in Descartes as he points to the delusions of madmen and melancholics to shake our faith in the reliability of ordinary perception. This strain, too, preceded Descartes, and had its foundations in classical skepticism as early as Sextus Empiricus, who argued that judgment could not be reached on the certainty of perception when a perceiver’s humoral disposition could color or manipulate it.

These natural and material accounts seem modern except that they build upon bases decidedly unmodern. The sensory system they build from remains firmly paramaterial at its core, but they also grow from and depend upon Galenic humoralism and quasi-Aristotelianism. Early modern skeptics, too, which resemble modern perspectives, often emerges through the discourses of Galenic medicine to trouble the reliability of perception and to argue that all perception is always-already colored by the individual perceiver. Despite these seeming similarities with a modern point of view, the theories of the sensorium emerging from those very same traditions offer the sensitive soul as positioned between the external and the internal, between the material and the immaterial, and between the external object and the mental object. While they acknowledge the shaping of species or phantasms by an individual perceiver, there is a relationship to the world established through them; a kernel of the real accessible to a perceiver. As Horatio claims of the ghost preserved in his memory after his encounter in I.i., it becomes a type of “mote” in the mind.

For the sixteenth-century translator of Sextus many assume to be Sir Walter Raleigh, the faculty responsible for such vulnerabilities is the phantasy or the imagination. Reason, the “Captain,” depended upon the objects and the evaluations offered by the phantasy, and, as du Laurens said, the phantasy could “misse-inform” Reason. The disordered phantasy affected judgment as well as perception, rendering, from a philosophically skeptical position, all perception and knowledge suspect. The phantasy, tasked with transforming sensory data into a form understandable to reason and the soul, remained linked to the body both in its situation within the brain, but also through the sensible spirits that filled it. The quality and condition of those spirits depended upon the humoral disposition of the humoral body as a whole, and a disordered mind could be the result of a disordered body which generated disordered or corrupt spirits. Such theories bring classical up to early modern theories in line with some contemporary movements in neurobiology. Such theories could classify mental as bodily problems and vice versa as coextensive and coexpressive, but, in the early modern period and previously, that point of connection and relation was often situated in the sensitive soul and especially its phantasy. For early modern skeptics rediscovering the classical skepticism of Sextus Empiricus, the phantasy or imagination was the sensitive soul’s point of vulnerability.

Responsible for the initial processing of sensible into mental species, problems within the faculty or within its spirits challenged the reliability of perception and the knowledge available through it. At the same time when mental objects theoretically retained a relationship to external objects, the fact that the recombinative phantasy produced new objects or altered existing ones challenged any unimpeachably secure mimetic bond. The system which theorized mimetic objects derived from the external senses as well as the produced objects in the phantasy grants the spectral objects of the mind a special ontological status. In effect, they become both present-absences and absent-presences. Such is the case with the phantasm of Old Hamlet within Hamlet’s “mind’s eye” which at once remains more linked to the one-time presence of the real dead royal father. The image in the faculty itself has an in-between status precisely by virtue of the process of mimetic-yet-quasi-material process which forged it within young Hamlet’s brain. At the same time, however, its appearance and substance in Hamlet’s mind bears with it a subjective sculpting, shaping, and framing. The model of the sensitive soul, however, granted those objects a paramaterial reality within the very substance of the mind.

Such a system could work in the opposite direction, granting the mental images that were the products of reading and other constructed phantasms a level of material reality. If I am correct to argue that vulgar understandings of the sensitive soul and it’s objects were granted a type of quasi-materiality, or, as I call it, paramateriality, then the new images formed in the phantasy either by reading or by dividing and recombining the parts of objects stored in the memory, they too would be granted a quasi-material or paramaterial status. Those paramaterial entities acquired through perception had their own affective power through the psychophysiological construction of the perceiver’s mind and body, and, so too, did the images constructed in the phantasy of the reader or audience member.

If I am correct that the images in the phantasy have a quasi-material or paramaterial presence in the early modern paramaterial mind, then the images constructed by the recombinative phantasy also, theoretically, has a quasi-material presence even in the absence of a truly external cause. In the context of the theater, the actors leave their presence, though a shaped one, within the minds of their audience. Becaue we are not yet to a cultural and historical situation where the objects of the eye have no relation to the objects in the mind, the audience is somewhat materially altered by their experience of the play, but wht remains “impressed” in their minds, the “mote to trouble the mind’s eye,” is somewhat an illusion, but has a quasi-material presence. The audience is left with illusory phantasms not all that dissimilar from those left by the Ghost within the world of the play.

Hamlet, Gertrude, and the Ghost during the Closet scene.